Gepubliceerd op 20 januari 2023

The campaign involved taking simultaneous measurements of sea ice from ESA’s CryoSat and NASA’s ICESat-2 satellites, and from an aircraft flying directly beneath the two satellites.

It is the first time that this has ever been done in the Antarctic.

CryoSat carries a radar altimeter and ICESat-2 carries a laser. Both instruments measure the height of ice by emitting a signal and timing how long it takes for the signal to bounce off the ice surface and return to the satellite.

Knowing the height of the ice allows scientists to calculate thickness – which, along with measurements of the extent of ice coverage, is vital for understanding how the volume of ice is changing, both ice on land and ice floating in the sea.

This is particularly difficult over sea ice because snow can build up on top of the ice.

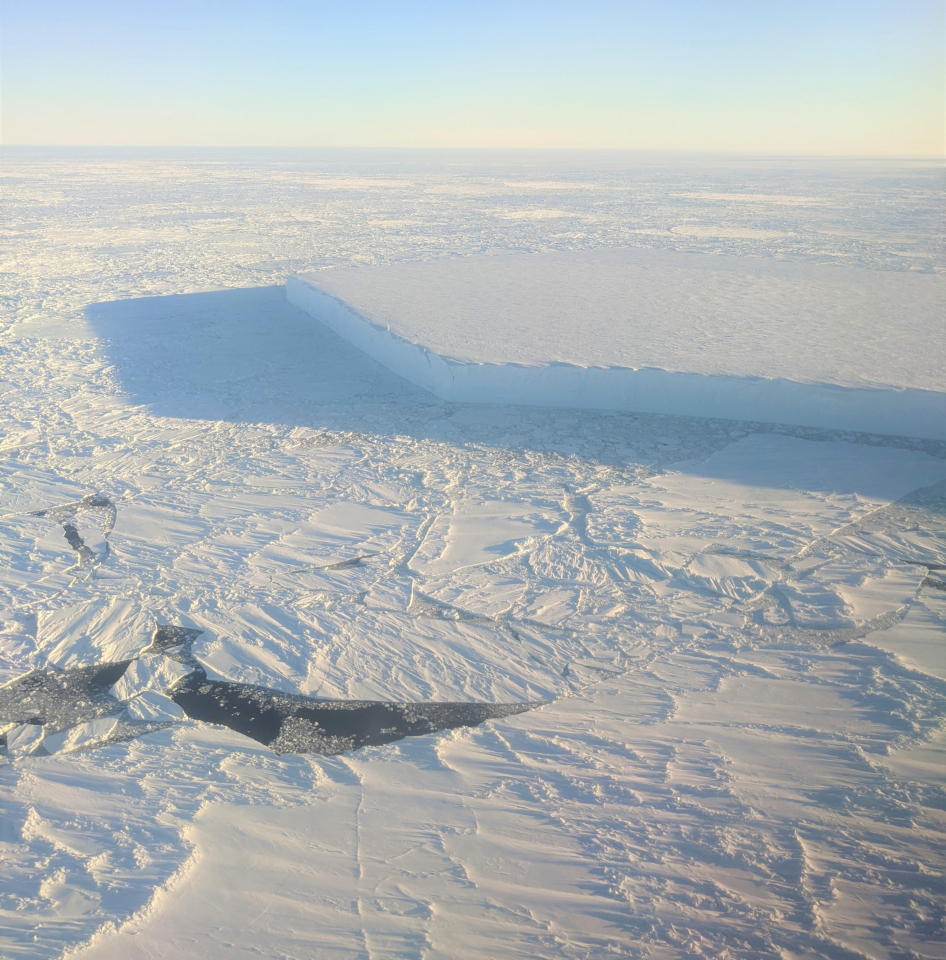

Weddell Sea iceberg

Determining the thickness of sea ice involves measuring the ‘freeboard’ of ice floes – the height protruding from the water. However, snow can push the floe down into the water, hiding the ice’s true thickness. A snow-loading correction therefore needs to be applied to the data.

Combining measurements from the two satellites allows scientists to correct for this snow-loading effect.

While CryoSat’s radar penetrates through the snow layer and reflects closely off the ice below, ICESat-2’s laser reflects off the top of the snow layer. Blending simultaneous satellite laser and radar readings means that estimates of snow depth will be more reliable.

However, currents and wind shift sea ice around. Under normal circumstances, the two satellites would take measurements over the same location days apart, so it could be different ice under their normal orbital paths. Ice on land is, of course, less dynamic.

Until now, scientists have not been able to fully exploit coincident measurements recorded by each mission to monitor sea ice in the Southern Ocean.

Source:

European Space Agency (ESA). (2023, January 19). Future-proofing ice measurements from space. https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/FutureEO/CryoSat/F…