Australia's Great Barrier Reef could lose 95 percent of its living coral by 2050 should ocean temperatures increase by the 1.5 degrees Celsius projected by climate scientists. World Worldwide Fund for Nature

The rainforest of the sea

Coral reefs are known as the “rainforests of the sea.” Covering less than 1% of Earth’s surface, they are home to one quarter of known marine fish species.

The reefs are formed by billions of small animals, polyps, living in a symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae called zooxanthallae. They need one another for shelter and food. Algae are plants and they use sunlight and CO2 to produce oxygen and food for their host polyp. Polyps protect the zooxanthellae, release CO2, and provide them with necessary nutrients from their own waste.

Each polyp lives inside a shell of calcium carbonate. The polyps join together to form the distinctive, intricate patterns of coral while the zooxanthellae give corals their colour.

Corals mainly thrive in tropical saltwater environments where the temperature is between 20 and 32ºC and the water is clear so that light can penetrate.

Source

The Great Barrier Reef

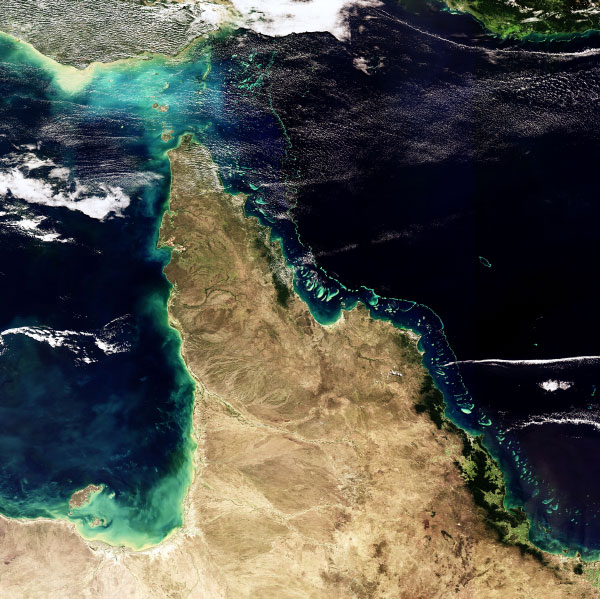

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest reef, stretching more than 2,300 km along the northeast coast of Australia and covering an area of 348,000 km². It is composed of 3,000 individual reefs and 900 islands. It is the world's biggest single structure made by living organisms.

An area of biodiversity equal in importance to tropical rainforests, the Reef was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981. Around a third of the Reef is protected as part of Australia's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, the largest marine park in the world. There are over 1,500 species of fish, 400 species of coral, 4,000 species of mollusc and 242 species of bird within the park, plus a great diversity of sponges, anemones, marine worms and crustaceans. It is home to dugongs, sharks, whales and dolphins and turtles.

This Envisat image features one of the natural wonders of the world – the Great Barrier Reef in the Coral Sea off the East coast of Queensland, Australia - Source: ESA

Bleaching

Coral reefs worldwide are increasingly under threat from coral bleaching. This phenomenon is associated with increased water temperatures (tropical ocean temperatures have increased 1°C over the past  100 years). The first coral bleaching on record occurred in 1979. Since then, there have been six events, each of which has been progressively more frequent and severe.

100 years). The first coral bleaching on record occurred in 1979. Since then, there have been six events, each of which has been progressively more frequent and severe.

Coral reefs are a fragile ecosystem and are very sensitive to sea temperatures outside their normal range. Unlike fish that can move to habitats with more suitable environmental conditions, corals cannot escape areas of high temperature because they are attached to the reef structure. If temperatures are too hot for too long, the symbiotic relationship between the polyps and the zooxanthellae collapses and the majority of zooxanthellae are expelled. Even small temperature increases, as little as 1 °C above normal temperature range, over a period of a week or more, can cause corals to expel their zooxanthellae.

The photosynthetic pigments in the zooxanthellae give the coral its distinctive colour, so when the number of algae in the tissues are greatly reduced, the corals become pale and look 'bleached'.

If high temperatures are relatively short-lived, the zooxanthellae that remain within the coral divide rapidly once the stress diminishes and the coral gradually regains its colour and survives. However, even corals that survive bleaching can suffer long-term effects such as reduced growth and they can be more susceptible to disease. If the stressful conditions are prolonged or particularly severe, the density of zooxanthellae remains low, and many corals will die.

Degree Heating Week

Degree Heating Week

One DHW is equal to one week of a sea surface temperature = 1ºC above the expected summertime maximum. Two DHWs are equal to two weeks at 1ºC or one week at 2ºC above the expected summertime maximum temperature. A DHW of 4 means that coral bleaching will occur in areas where there are coral reefs.

Sea surface temperature (SST - dark-blue line) and coral bleaching Degree Heating Weeks (DHW - solid red line) from January 2002 to December 2003 for the Davies Reef. The corresponding thermal condition related to coral bleaching is color-coded and plotted below the time series. The thermal condition is categorized in the five bleaching alert levels. Source: Coral Reef Watch's Satellite Bleaching Alert - NOAA

Source

Bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef

Since 1978, six mass bleaching events took place, triggered by unusually high sea surface temperatures. Most widespread events have occurred in 1998, 2002 and 2006, affecting up to 50% of reefs within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Mortality was distributed patchily, with the greatest effects on near-shore reefs.

Sea temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef have warmed by about 0.4°C over the past century and rising sea temperatures, are almost certain to increase the frequency and intensity of coral bleaching events.

Source

Under a moderate warming scenario, corals are very likely to be exposed to regular summer temperatures that exceed the thermal thresholds observed over the past 20 years and annual bleaching is projected by 2030 to 2050. Given that the recovery time from a severe bleaching-induced mortality event is at least 10 years, reefs may be dominated by non-coral organisms such as macroalgae by 2050.

Map showing bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef as seen from aerial surveys in 2002.

Source: CRC Reef Research Centre

Sources

IPCC Report Australia and New Zealand

ReefBase: A global Information System for Coral Reefs

Satellite Coral Bleaching Monitoring - NOAA

Symbiosis - Harvard College Teacher's resource website

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park - Australian Government

This page was written in 2009, as additional information to the poster series "10 years of Imaging the Earth"