Gepubliceerd op 6 oktober 2022

Although methane partly dissolves in water, released later as carbon dioxide, it is not toxic, but it is the second most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas in our atmosphere causing climate change.

Although methane partly dissolves in water, released later as carbon dioxide, it is not toxic, but it is the second most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas in our atmosphere causing climate change.

As the pressurised gas leaked through the broken pipe and travelled rapidly towards the sea surface, the size of the gas bubbles increased as the pressure reduced. On reaching the surface, the large gas bubbles disrupted the sea surface above the location of the pipeline rupture. The signature of the gas bubbling at the sea surface can be seen from space in several ways.

Owing to the persistent cloud cover over the area, image acquisitions from optical satellites proved extremely difficult. High-resolution images captured by Pléiades Neo and Planet, both part of ESA’s Third Party Mission Programme, showed the disturbance ranging from 500 to 700 m across the sea surface.

Several days later, a significant reduction in the estimated diameter of the methane disturbance was witnessed as the pipelines’ gas emptied. Images captured by Copernicus Sentinel-2 and US Landsat 8 mission confirmed this.

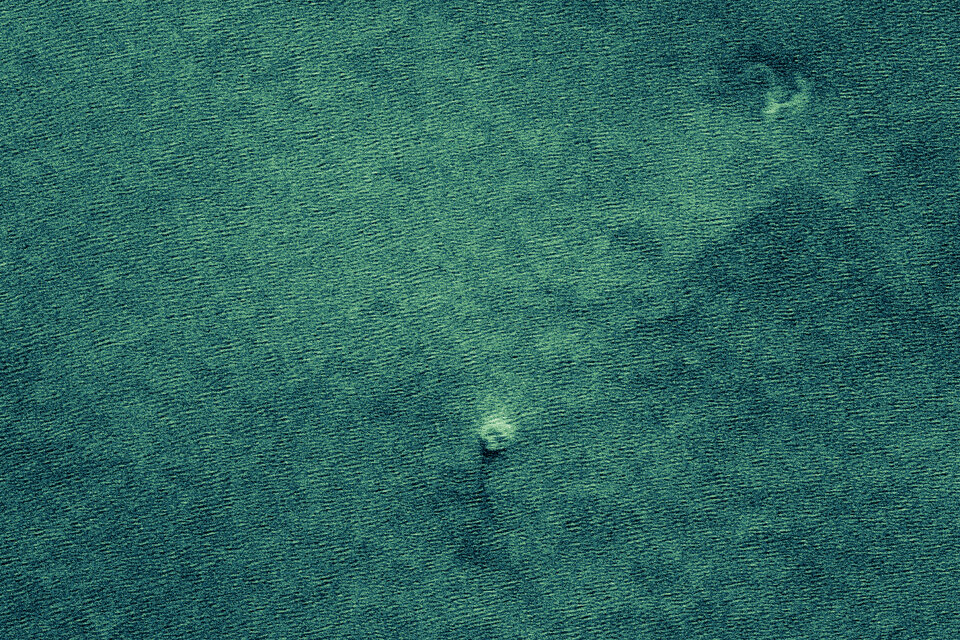

As disturbances such as these cause a ‘roughening’ of the sea surface, this increases the backscatter observed by Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) instruments, which are extremely sensitive to changes in the sea surface at such a scale. These include instruments onboard the Copernicus Sentinel-1 and ICEYE constellation – the first New Space company to join the Copernicus Contributing Missions fleet.

ESA’s Scientist for Ocean and Ice, Craig Donlon, said, “The power of active microwave radar instruments is that they can monitor the ocean surface signatures of bubbling methane through clouds over a wide swath and at a high spatial resolution overcoming one of the major limitations to optical instruments. This allows for a more complete picture of the disaster and its associated event-timing to be established.”

One of the ruptures occurred southeast of the Danish Island of Bornholm. Images from Sentinel-1 on 24 September showed no disturbance to the water. However, an ICEYE satellite passing over the area on the evening of 28 September acquired an image showing a disturbance to the sea surface above the rupture.